Why do I continually go on about the importance of innovative work of your own, about the pleasure to be taken from it? Why do I think it a good idea at all? These are not questions I can answer, they are the questions that bug me all the time.

Why do I continually go on about the importance of innovative work of your own, about the pleasure to be taken from it? Why do I think it a good idea at all? These are not questions I can answer, they are the questions that bug me all the time.

On the other hand I know that when I am in the middle of good and innovative work it simply feels right. It has value to me. And although this value is hard to define, or perhaps because it is hard to define, I was delighted to be reminded of an entire book dedicated to the subject of this value, and the fact that it is difficult to define.

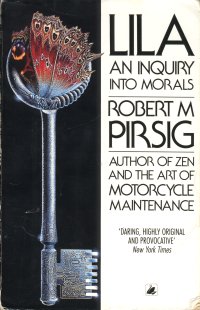

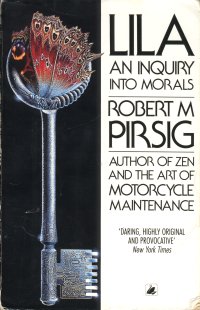

Lila: an Inquiry into Morals was a favourite of mine in my twenties – one of those youthful doses of heady philosophy whose ideas feel like they have permanently expanded your perspective on the world. (Which is a good reason for never re-reading such books, if your more ambivalent older self has a more cynical attitude towards what they have to say.)

But a re-reading of Lila was a pleasant surprise, because the ideas still resonated. Not only resonated – the book provided me with a label for The Tyranny of Career‘s pleasure-from-innovative-work which I have had a hard time trying to define: Dynamic Quality.

Lila’s central idea (which follow on from the ideas in Pirsig’s 1970s cult bestseller Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance) is what Pirsig calls his metaphysics of quality. The idea that we can better understand the world if we think of it not as a material world, of subjects and objects, but of patterns of value. By which he means the cause of change in the world, at all levels, whether biological, social or intellectual, is through the preference for one pattern of value over another.

An example on the biological level might be that one human being values another’s physical appearance, which causes them to want to desire sex. On the social level a human being might value the stability and security of a relationship and family over the chance to have sex with as many people as possible. On an intellectual level, the value is at the level of ideas – the idea that we should not ostracise a person from society (such as happened in Victorian times) simply because they decide not to marry or have children.

Each of these different categories of value is separate from the others. Not only separate, but they work against each other, both within individuals and within society itself. The social value we place in a family works against the biological value for sex with multiple attractive people. The intellectual value of freedom-to-live-how-you-want works against the social value of promoting the nuclear family as the right way to live.

The different levels of value fight against each other not in the sense of one defeating another, but in the sense that they remain in constant tension. They are the source of tension in human lives, in society – they are the explanation for why the world appears in a messed up state. We value the intellectual pattern of value of equal rights for all, but, if we are Westerners, this fights against social instincts to keep our privileged status in the world. These tensions exists in all of us, to greater and lesser degrees.

(This is a very brief overview of the book’s ideas – I’ve read it four times now and I’m still finding new insights. If I haven’t explained it clearly – well, you’ll have to read the book yourself.)

How does this relate to pleasure from innovative work? The examples described above, of sex with attractive people, family, the right to live as you please, are patterns of value that we recognise because they are familiar, are widely recognised. Pirsig calls these familiar patterns static patterns of value, and the value contained in these patterns he calls static Quality (Quality with a capital Q is something he defines at great length in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance). The static Quality of the human body keeps it in one piece; the static Quality of traditions such as the nuclear family keep a society in a stable state.

But beyond static Quality there is another type of quality: Dynamic Quality. Dynamic Quality is a new pattern of value, in the intellectual sense a new idea, but one whose value is not widely accepted. Martin Luther King’s ideas about civil rights contained Dynamic Quality. The inventiveness in the films of Michel Gondry contain the same.

And Dynamic Quality can be used as the definition of what we seek when we do innovative work of our own. This Dynamic Quality is what we want to feel, to experience. We recognise it when it happens, and know when it is not happening, but it is very hard to say what Dynamic Quality actually is. It is what happens during flow, when you lose track of time. It is not limited to the ‘arts’ – it could equally be found in the idea for a successful fundraising drive for a charity.

As described above Dynamic Quality might be thought of as a synonym for creativity. But I do not think there is an exact correlation – Dynamic Quality is more ‘the thing which causes the pleasure from creativity’. It is what we look for, all our lives, in every aspect of our lives, without realising.

Dynamic Quality is not, needless to say, something readily found in a traditional career working for someone else. Rather a constant rediscovery of Dynamic Quality is a good definition of a successful self-made career. It is what keeps us going in life.

Recent links on careers, fulfilling work and writing:

This week I was discussing with a friend the importance of mentors for your own work. Someone who has experience of whatever it is you are trying to do, who can be a good source of knowledge for the progress of your work. To whom you can ask questions.

This week I was discussing with a friend the importance of mentors for your own work. Someone who has experience of whatever it is you are trying to do, who can be a good source of knowledge for the progress of your work. To whom you can ask questions. Why do I continually go on about the importance of innovative work of your own, about the pleasure to be taken from it? Why do I think it a good idea at all? These are not questions I can answer, they are the questions that bug me all the time.

Why do I continually go on about the importance of innovative work of your own, about the pleasure to be taken from it? Why do I think it a good idea at all? These are not questions I can answer, they are the questions that bug me all the time.